シプナックの『LIV and Let Die』でも大いに参考にされた記事ですね。

LIVという怪物ができるまで|シプナック『LIV and Let Die』 - Linkslover

PGAツアーができたいきさつは,いまのPGAツアー対LIVの構図に似てなくもないというか。

ソース

The Day the PGA Championship nearly died: War for the Tour by Jim Gorant, 8 Aug 2018

拙訳

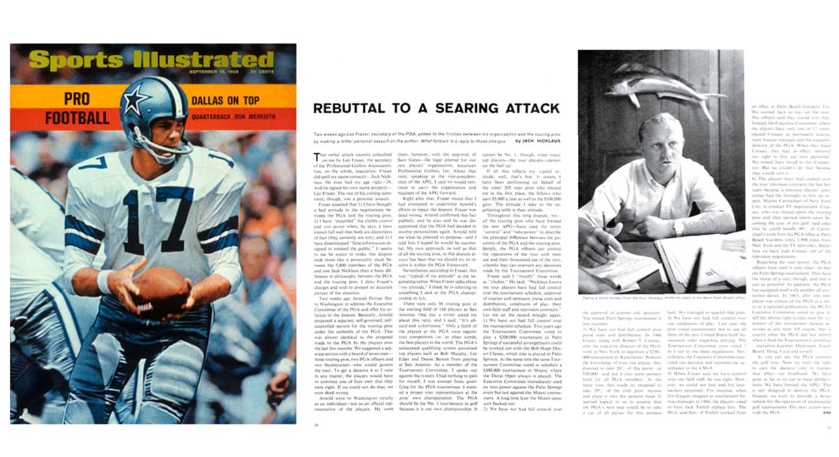

「プロゴルフ協会(PGA)の書記であるレオ・フレイザーが最近私に放ったあの口撃は,全体として不正確だった。フレイザーは私の名前――ジャック・ニクラス――を正しく綴った。彼は私の年齢――28歳――さえもを正確に言った。そして彼は自分の名前――レオ・フレイザー――できちんと署名した。しかし,彼の痛烈な発言の残りの部分は,個人攻撃だった。」 *1

このようにして,Sports Illustrated 誌の1968年9 月16日号にエッセイが始まり,おそらくこのゲームの最も偉大なプレーヤーが,PGAの最高位の役員のひとりと対戦した。これは,ほぼ2年間続いた組織団体に対する選手の反乱の中で放たれた多くの一斉射撃のひとつであり,それによって1968年の年間最優秀選手賞は取り消され,複数の法的訴訟を引き起こし,PGAを永久に分裂させた。 *2

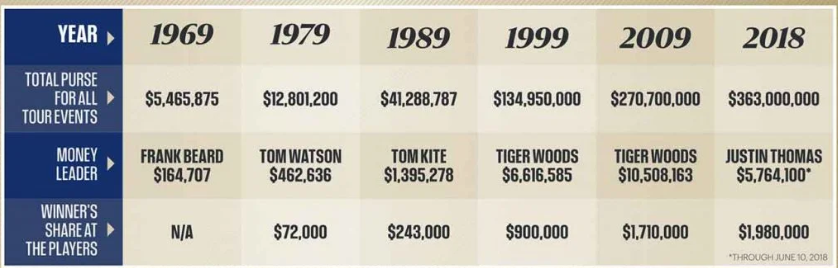

何がそのトラブルの原因か? ほかに何があるだろうか。機会,お金,権力―― コントロール。壮大かつ苦い対決の結果はどうなるか? 今日私たちが知っているこのプロゲームは,トーナメントの名前が企業,慈善団体,ホスピタリティパビリオン,豪華な送迎車,そして賞金などにつけられており,2017年に賞金ランキング102位の選手(スティーブ・ストリッカー)が13試合に出場して100 万ドル以上(100万2036ドル)稼いだほどだ。 *3

「多くの選手は,もともとPGAとの争いに反対していました」と,トーナメント委員会のメンバーとしてこの運動の首謀者のひとりだった89歳のボブ・ゴールビーは言う。「リーダーシップ委員会の委員を務めていない選手たちは何が起こっているのか理解していなかったが,一度真実を見聞きしたら,彼らは同意したのです。」 *4

戦線が強化されるにつれ,ニクラウスは200人以上の選手たちの中でリーダーとして浮上した。選手たちは,クラブプロによって設立されクラブプロのために運営されている組織からより良い条件をもらわなければ,バラタと保証金を取り上げると脅している。PGA会長のマックス・エルビンがオールドガードを率い,PGAの非ツアー会員やウォルター・ハーゲン,サム・スニード,ニクラウスの少年時代のアイドル,ボビー・ジョーンズなどの重鎮がサポートした。当時のゴルフ界で最も強力なプレーヤー,アーノルド・パーマーは,どっちつかずな状態だった。 *5

「最初の亀裂を引き起こしたのは何だったか?」 と,1967年から73年までツアーに参加したディーン・ビーマン(80歳)は尋ねる。「200人の選手が生活のためにプレーし,6000人のクラブプロが定職に就いていたが,これらふたつのグループのニーズはもはや一致しなかった」。闘争を決定づける質問は単純なものだった:相手のグループをより必要としているのは,どちら側か? *6

敵対行為の真っ最中でも,メリーランド州ベセスダの Burning Tree のヘッドプロ,エルビンは屈する気配を見せなかった。「困難を引き起こした人の中には,有能な選手を新たに育成するのにどれだけ時間がかからないかを知って驚く人もいるかもしれない」。 *7

負けじと,選手たちに雇われているニューヨーク州の弁護士サム・ゲイツも,どちらが優位かという質問に対して,完全に敬意を表したわけではないにしても,より簡潔に答えた。「ここは」と,脱退グループについて彼は言った。「踊っている女の子たちがいる場所ですよね?」 *8

1. 設立|The Establishment

アメリカプロゴルフ協会(PGA of America)は,プロショップを経営しレッスンを行なうゴルフプロの組織として,1916 年に設立された。北部の州では多くのクラブが冬季休業となるため,そこで汗を流すプロたちは出稼ぎで南へ向かい,トーナメントに出場した。PGAがそれらイベントを主催しはじめ,1930年代までに冬季ツアーはある程度安定し,毎年多くのイベントが開催され,プレーヤーも安定して集まった。 *9

それでも小さな賞金額――商工会議所や観光を盛り上げようとするリゾートが通常提供する――では,誰もが生きていくのに十分ではなく,天候が変われば選手たちは家に帰って〈本職〉に就いた。それは1950年代まで続き,そこでイベントのスケジュールが拡大し,賞金額が十分に大きくなり,一部の選手はフルタイムでツアーに参加することを決めた。突然,PGAにはふたつのグループができた:ゴルフプロたちと,プロゴルファーたち。 *10

60年代を通じて, 人口動態の変化と,冒険家パーマーとテレビというふたつの変革勢力の合流によって,これらふたつの派閥間の溝はさらに広がった。1958年,ツアーでの賞金総額は100万ドルにとどまっていた;68年までにその額は560万ドルに達した。その現金をめぐる競争はダーウィン的だった。毎年,トーナメント優勝者と前シーズンの賞金上位60名には免除ステータスが与えられたが,そうでなければ,フィールドは月曜日の予選通過者で埋まった。 *11

これらの予選には,ツアーの常連選手だけでなく,プロショップから1週間休みをとってトロフィー獲得を目指す地元のPGA会員も参加できる。1964年までに,ツアーに参加する選手の数が非常に多くなり,出場権を争う地元のプロが非常に多くなったため――ツアー常連からの不満が非常に多かった――,PGAは選手がツアーカードを獲得できる予選トーナメント(のちにQスクールと呼ばれる)を創設した。カード所有者は免除者の仲間入りはしなかったが,月曜の予選に100ドルで参加できる――非カード所有者はいまや200ドルを払わなければならなくなったのに対して。さらに,カード非所有者がに与えられる枠の数には上限があった。 *12

ほとんどのフィールドの参加選手数は144名または156名で,免除された選手を含めると,毎週150名もの選手が50~75の枠を争っていたことになる。ツアープロにとって,リスクは大きかった。予選を通過するかどうかに関わらず,彼らは参加費,食費,交通費,宿泊費,キャディー代を支払わなければならなかった。 *13

プレーヤーたちは小切手を獲得する機会を切望していたので,1966年にフランク・シナトラがパームスプリングスで新たに20万ドルのトーナメントのスポンサーになると申し出たとき,彼らは興奮した。当時PGAのトーナメント事務局として知られていたものは,4人の選手と3人のPGA幹部――エルビン,フレイザー,会計担当のウォーレン・オーリック――で運営されていた。投票の結果4対3で,委員会はシナトラのイベントをスケジュールに追加することを決定した。 *14

エルビンがオール・ブルー・アイズ(訳者注:シナトラ)の計画に反対していた理由は,このイベントが同じくパームスプリングスの大会である Bob Hope Desert Classic の数週間以内に開催されるためであり,ホープ自身も両方のイベントが存続できるとは思わないと述べたからだ。トーナメント委員会の決定は,役員16名と選手1名からなる17名のPGA執行委員会の全員の投票の対象となる。そのグループの次回の集まりを待つ代わりに,エルビンは出席している執行委員会のメンバー4名――役員3名と選手代表――に,委員会全体を代表して投票するよう呼び掛けた。結果は3-1で,臨時の執行委員会がトーナメント委員会の結果を覆した。 *15

選手たちは抗議した。「我々はあらゆるリスクを負っている」と,あるツアー競技者は当時SIに語った。「だったらどうして我々があまちゃんのクラブプロたちに,20万ドルのゴルフトーナメントには出場できなって言われなければならないんだ?」 *16

ツアープロたちはまた,ニューヨーク州ウェストチェスターでの新たな賞金25万ドルのトーナメントについても異議を唱えたが,このトーナメントはPGA幹部らが秘密裏に交渉し,その賞金のうち5万ドルが全PGA会員の一般年金基金に充てられる予定だった。その計画は取りやめになったものの,被害は出た。 *17

PGAにとって,そのシナトラのイベントは52年の歴史で初めて拒否権を発動する大義名分となった。 *18

選手たちにとって,それは戦争行為だった。 *19

2. 蜂起|The Uprising

不和は1966年末から1967年初頭まで続いた。ツアープロたちは〈セーターフォルダー〉による束縛にイライラし,一方クラブプロたちはテレビでそれを煽る〈プリマドンナたち〉にうんざりしていた。1964年にツアーに参加したカーミット・ザーリー(76)は,「ツアーのメンバーとして,しばらくはゴルフクラブのプロショップに行くのがあまり心地いいものじゃなかった」と語る。 *20

「問題は,3人のクラブのプロがパートタイムで運営全体をしていたことだった」と,ゴールビーは言う。「彼らには,年金からコース設定まで,私たちが必要とするすべてを処理する時間がなかった。しかし彼らは,それができたとき,クラブのプロが行なうようにそれに取り組んだんだ」。エルビン,オーリック,フレイザー以上に,ツアーメンバーたちは、トルーマン政権の元労働次官補ロバート・クリーシーに異議を唱えた。クリーシーは,選手たちの意向に反し,PGAによってトーナメントマネージャー兼エグゼクティブディレクターに任命されていた。 *21

クリーシーは係争中のウェストチェスター大会の交渉において重要な役割を果たしており,選手たちは彼がツアーに対してPGA当局がとった高圧的なアプローチの象徴であると感じた。選手たちは,彼がテレビ契約からスケジュールまであらゆることに口を出し,自分を〈ゴルフ界の皇帝〉にしようとしたと不満を述べた。ゴールビーは,ある会議のことを特によく覚えている:「私たちはトーナメント事務局に請求される費用について話していたのですが,クリーシーは『ボブ・クリーシーは旅行するときはファーストクラスの2倍になる』と言ったのです。それは多くの人にとってあまり良くありませんでした」。 *22

6月1日,メンフィスでは悪い感情が頂点に達した。選手たちは7項目のマニフェストを作成。スケジュール,財政,ツアー関連要員の雇用の管理を要求した。何よりも,彼らはPGAの拒否権を剥奪することを主張した。合計135人の選手が署名し,最後通牒も付け加えた。6月15日までにPGAがすべての意見に同意しなかった場合,選手たちは7月20日にデンバー近郊の Columbine Country Club 開催される1967年 PGA Championship をボイコットするというものだった。 *23

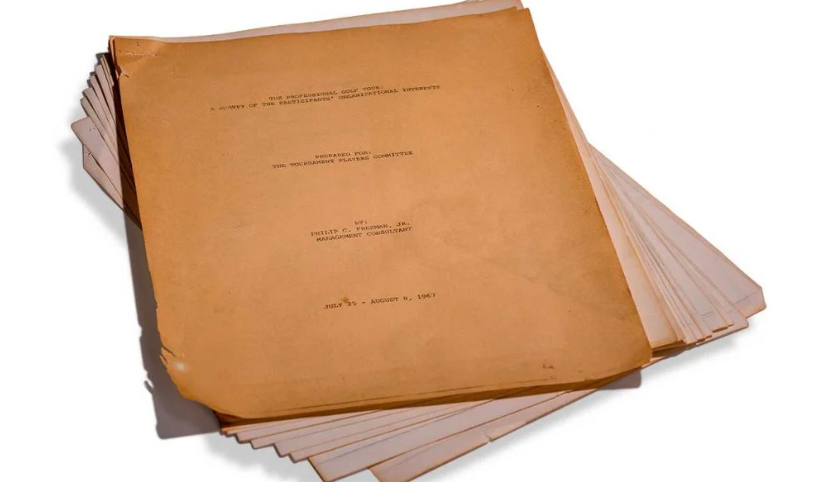

翌日,エルビンは記者団に対し,PGAはこの文書を検討すると語った。6月15日はUSオープンの初日だったため,同氏は6月20日にクリーブランドで選手たちと会う予定を立てたが,その前にツアーリーダーらを「扇動者」と呼び,「多くの選手は少しの真実とほのめかしとあからさまな嘘で餌付けされた痕跡を盲目的に従っているだ。」と発言した。 *24

次の2週間,両チームはジャブを打ち合った。エルビンは選手たち手紙を送り,ボイコットすれば出場停止になる可能性があると示唆したが,1957年のマスターズ優勝者で選手たちの非公式の〈苦情処理委員長〉であるダグ・フォードは,これを選手たちが「一笑に付した」と述べた。コミットした大会を欠場した場合,ルール上は高々100ドルの罰金が課されるだけだったから。 *25

この積み重ねにより,ニュージャージー州スプリングフィールドの Bultusrol でのUSオープンの週は,異常に緊張感の高いものになった。「パーマー,ディフェンディングチャンピオンのビル・キャスパー,そしてその他のスター選手たちは,練習ラウンドの合間にPGAの首脳陣との非公開ミーティングに慌ただしく出入りしていた」と,スパルタンバーグ・ヘラルド紙が6月14日に報じた。キャスパーは嘆願書に署名していなかったが,それはその時メンフィスにいなかったからにすぎない。「私は選手たちと一緒だ」と,彼は記者団に語った。「私は彼らに票を入れるよ」。 *26

クリーブランドではそのような団結が不可欠であることが判明した。9時間におよんだ会議では,辛辣な言葉や膠着状態もいくつかあったが,最後のセッションで妥協に至った:7人制のトーナメント委員会は,4人の選手と4人のPGA幹部からなる8人制のグループになるというものだった。投票が同点になった場合や紛争の場合は,選手たちが指名しPGAが承認する新しい3人からなる諮問委員会によって解決されることになる。選手たちはマニフェストに盛り込まれた7つの要求のうち,クリーシーのエグゼクティブディレクター解任を含む6つを獲得したが,PGAの拒否権はそのまま残った。 *27

「良い和解だ」と,フォードは後に語った。「結果に満足しているよ」。 *28

その喜びは,長くは続かなかった。 *29

3. 核のオプション|The Nuclear Option

選手たちは拒否権の存続について不平を言いつづけた。7月1日,フォードはツアーメンバーが再度投票を行い,クリーブランドの解決案を否認することを選択したと発表した。彼らは PGA Championship に出場したが,諮問委員会を任命することはなく,依然として執行委員会の管理権の剥奪を望んでいた。クリーブランドで双方が合意に達したと考えていた合意は,14日間続いた。 *30

その後の選手ミーティングで,アル・ガイバーガーは,経営コンサルタントとして働いているフィリップ・フリーマンという友人がいること,そしてそのフリーマンが志願して3週間を費やすことにすることに決まったと発表した。そこで彼は,選手,スポンサー,トーナメント関係者,PGA会員たちにインタビューすることで状況を分析し,問題点を特定する。その後,問題を解決するための提案も作成することになる。 *31

1967年8月8日,フリーマンは23ページの報告書を提出し,PGAとトーナメント部門をひとつ屋根の下に収容されるふたつの別個の組織にするよう,勧告した。PGAは現在の体制で運営を継続し,ツアーは選手会と外部の専門家によって監督され,日常業務と長期的な事業を運営するためにコミッショナーを雇うことになる。同氏は選手たちに,交渉の代理人として弁護士を雇うことを提案した。 *32

選手たちはその報告書を読んだが,何も行動を起こさなかった。少なくとも,11月にフロリダ州パームビーチで開催されるPGA年次総会までは。そこでエルビンが,「ルールに従うか,出ていくかだ」という警告を含むスピーチをした。 *33

彼の態度は「嫌がらせにうんざりしていた」ことが一因だと説明した。彼がツアー選手に言及していることが明らかでない場合,彼は新しいトーナメントエントリーフォームの導入を進めた。それは,選手の権利を制限し,PGA Championship の出場資格のある人なら誰でも出場することを義務付けるものだった。「我々のレギュラーツアーイベントの参加者は,我々のチャンピオンシップに出場する義務があるとみなされる」と,彼は語った。それを反ボイコット条項と呼ぼう。 *34

トーナメント委員会を8人で拡大するというクリーブランドで合意された計画は存続し,年次総会では選手たちは委員長としてガードナー・ディキンソン,ダグ・ビアード,フォード,ニクラウスで半数を占めた;幹部の半分はエルビン,オーリック,フレイザー,そしてバイスプレジデントのノーブル・チャルファントで構成されていた。グループは冬の間,USGAの新しいパッティング規制――執行委員会は当初承認したが,選手たちは猛反対した――と,新しいトーナメントエントリーフォームをめぐって戦いを続けた。 *35

Crosby Clambake で1968年シーズンが1月に始まったとき,いずれの問題も解決されていなかった。選手たちはゲイツを雇ったが,ゲイツは新しいフォームを受け入れないようアドバイスした。合法的な勢力に支援された大規模な反乱に直面して,PGAはパッティング規制に関して選手たちを支持し,古いエントリーフォームに戻した。また,ワシントン州の弁護士ウィリアム・ロジャースという独自の代理人も雇った。 *36

次の数か月間,ゲイツとロジャースは対話を続けた。すべての当事者に友好的な和解交渉ができることを保証しながら。「私たちは何度も何度も電話したり会ったりしました」と,ゲイツは語った。「私たちの間には,争いは一切ありませんでした」。 *37

平和は伝播しなかった。選手たちは核オプション――PGAを完全に放棄して独自のツアーを始めるという――を検討しているという噂が流れた。選手たちを勇気づけたかのように,PGAは7月下旬,ボブ・クリーシーをエグゼクティブディレクターとして再雇用した。こんな噂が広まった:彼が選手たちに相談せずにワールドシリーズ・オブ・ゴルフとシェルのワンダフル・ワールド・オブ・ゴルフのテレビ契約を10万ドルで交渉し,そのお金がトーナメント事務局ではなく一般のPGA基金に繰り入れられるという。選手間で議論が巻き起こった。「そのミーティングの中では,感情的になるものもありました」と,ザーリーは振り返る。 *38

サンアントニオの Pecan Valley で開催された PGA Championship で予選落ちした後,ジャック・ニクラウスは,112人のクラブプロとわずか56人のツアープロが含まれるこのフィールドについてどう思うかと尋ねられた。「不条理だし不幸だ」とゴールデンベアはうなり,それに対してPGAは憤慨した。 *39

8月初旬,状況はさらに悪化した。 *40

ロジャースとゲイツは,PGA の屋根の下で運営される自治トーナメント部門の枠組みを描いていた。部門がどの程度自律的になるかについて詳細を整理するのは,困難な部分だった。PGA規約の改正は11月の年次総会の100日前までに提出する必要があったため,ゲイツはこの問題が確実に議事録に載せられるよう,1968年8月6日に代替決議案を提案した。この文書の一部には,PGAのトーナメントプレーヤーズセクションが,「PGAトーナメントプログラムの実施と管理に関して,全面的かつ完全な権限を持つものとする」ことが求められていた。 *41

エルビンと同僚は,反対票を投じた。 *42

ゲイツは激怒した。「議題は単純なもので,2分もかからないはずだった」と,当時ゲイツは語った。「この行動は,更なる交渉への扉を開いたままにすることだけを目的としたものだった。しかし,PGA役員はそれを私たちの顔に叩きつけたんだ」。彼はさらにこう語る。「ロジャースと私との間で何ヶ月にもわたって辛抱強く努力し、意見の相違を公正に解決するために我々が進めてきたすべての成果を,そうすることで役員たちは完全に台無しにしてしまった。悪意の表れとして,彼らは痕跡を蹴り飛ばしたのです」。 *43

「選手たちはいまや,PGA の他の部分から完全に独立することを望んでいた」と,エルビンは答えた。「これは全く容認できないものだった」。翌週,ゲイツはワシントンD.C.を訪れてPGA幹部と会談したが,彼らはクリーブランド協定を復活させる試みと思われる8項目の計画を提案した。その中で,紛争を仲裁する諮問委員会の設置を提案した。しかし,この計画によりPGAは取締役会の支配多数派となり,拒否権が事実上維持された。 *44

今度はゲイツがこの取引を拒否した。その後の交渉は決裂し,その日遅く,Westchester Classic のために集まった100人以上の選手が投票を行なった。当面の問題は,米国のプロゴルフの将来だった。満場一致で,ツアープロは核武装した。 *45

4. 膠着|The Standoff

「私には205人の顧客がいます。数えてみました。私たちは現在,トーナメントとテレビ契約について交渉中です。完了したら発表いたします」。それは,選手たちが離脱を投票してから6日後の8月19日のことで,ゲイツはAPG(American Professional Golfers, Inc)を紹介する記者会見を行なっていた。13人のメンバーで構成されるAPG諮問委員会――ディキンソン,ニクラウス,ビアード、フォード,キャスパー,ゴールビー,ザーリー,ジェリー・バーバー,ライオネル・ハーバート,デイブ・アイケルバーガー,デイブ・マー,ボブ・ロズバーグ,ダン・サイクス――が生み出された。 *46

ゲイツの発表では,選手たちはシーズンの残りと,すでに1969年に契約を結んでいる2つのトーナメントをプレーする。「うちの選手たちはPGAを辞めるつもりはない」と,彼は語った。「選手たちはいかなるトーナメントもボイコットしない。なぜなら,それはゲームにとっても大衆にとっても最善の利益ではないからだ」。 *47

「我々はPGAの代表権を剥奪したくない」と,ディキンソンは言った。 「私たちが望んでいるのは,どこで,どのように,どのような条件でプレーするかといった問題について,決定的な投票を行う権利を持つことだ。それは私にとって合理的な要求のように思えます」。 *48

エルビンはそうは思わなかった。その2日前,PGAはトーナメント委員会を解散してツアーの管理権を掌握し,APGと同じ日に独自のプレスサミットを予定していた。「彼らがPGAから逃げたいという願望が見えない」と,エルビンは語った。「理解できないね。PGA はこれらの人々の中から億万長者を生み出したんだ」。 *49

エルビンはラインをまたぐ余地を残さなかった。「選手が他のグループに所属することを決めた場合,その選手のPGAカードは直ちに解除される」。PGAイベントがどうなるかについては,「トーナメントゴルフは継続する。最初は大変だと思うが,耐えていくよ」。 *50

これらの方針に沿って,フレイザーは,PGA が依然としてクラブプロを管理し,したがってクラブを管理していると指摘した。「私たちには6000の小さな工場があり,潜在的なスターを輩出している」と,彼は言った。 *51

翌日,エルビンはプレーヤーにPGAへの参加を強制する新しいトーナメントエントリーフォームを提案した。辞任したディキンソンは,「今のところ和解の可能性はない」と認めた。 *52

5. 和平協定|The Peacemaker

アーノルド・パーマーほど,分裂に葛藤している人はいなかった。彼は公に選手たちを支持していたが,双方との対話を続けていた。「彼はクラブを売っていたので,クラブプロたちを遠ざけるのは難しかった」と,ゴールビーは言う。「彼らがパーマーのクラブを取り扱うのをやめてしまうのではないかと,彼は心配しなければならなかった」。 *53

クラブの販売のほかに,パーマーは儲かるスポンサー契約を結んでいてゴルフ以外にも悪名が広く知られていたため,彼と代理人のマーク・マコーミックは,世間から否定的な目で見られることを懸念していた。何よりも,パーマーの父ディーコンは Latrobe Country Club のヘッドプロであり,長年PGA会員であった。この組織はパーマー個人にとって大きな意味を持ち,彼は和解せざるをえないと感じた。APG設立後,彼は「プロとPGAはお互いを必要としていると思う。さらなる交渉が必要だ」と語った。 *54

パーマーはあちこちに電話をかけ,8月23日金曜日,エルビンは彼に会うためにラトローブに飛んだ。6日後,パーマーは恩返しをし,PGA執行委員会でプレゼンテーションを行なうためにワシントンD.C.に飛んだ。パーマーはAPGの代表ではなかったが,ゲイツは渡航を承認した。「個人としての私の目的は,解決策を見つけようとすることだ」と,パーマーは語った。 *55

4時間半に及んだ非公開セッションでパーマーは,1年間のトライアルとして2つのグループを合併すべきだと主張し,その間ツアーは14人からなる理事会――APGの新たに選出された7人の選手と役員(会長のディキンソンと副会長のニクラウスを含む),4人の無所属の実業家,3人のPGA役員――によって運営される。エルビンは,PGA諮問委員会全体が9月6日にヒューストンで開催する会議でこの提案について話し合うことを約束した。「アーノルド・パーマーと話すときはいつも,それは正しい方向への一歩だ」と,彼は語った。 *56

「当時,アーノルドはゴルフに関してかなりのことを操っていた」と,ゴールビーも同意する。 「他の選手たちは彼の意見を尊重した」。もしアーニーがPGAに残ると言ったら,多くの人がそれに従っただろう。 *57

しかし,ゴルフ界の他のビッグスターはすでに去っていた。パーマーが交渉している間,ニクラウスはAPGが計画を進めると主張した。そのためフレイザーは,ジャックがアーノルドの努力を台無しにしようとしていると非難した。ニクラウスが「国民を誤解させることを目的とした虚偽の情報」を流布したなどというフレイザーの主張は,Sports Illustrated 誌でのニクラウスの1500語に及ぶ痛烈な反論につながった。 *58

両勢力の外側では,他の強力な勢力が動きはじめていた。PGAの44大会のうち34大会の資金を代表する国際ゴルフスポンサー協会(IGSA)は,1968年の残りのシーズンを危険にさらさないよう双方に警告した。PGA Championship を含む10のツアーイベントを放映する2年契約を結んだばかりのABCでは,当時同局のスポーツ担当VPだったルーン・アーレッジが声を上げた。「現在の論争が我々にどのような影響を与えるかは分からないが,誰も参加しないトーナメントをテレビ放送するつもりはない」と,彼は語った。 *59

6. 分裂|The Breakup

ヒューストンが問題になった。PGA諮問委員会の会合に合わせて,IGSAは市内で年次総会を開催していた。パーマーの提案に関する議論が始まると,スポンサーたちは独自の解決策を提案した。それは,そのテーマの変奏曲だった。独立したツアー部門は,この場合,現役選手3名,引退選手3名,PGA幹部3名,IGSA役員3名で構成される12名の理事会によって統治されていた。 *60

新たな選択肢に直面して,PGAは決定を遅らせた。一方,コネチカット州の Greater Hartford Open では,関係者が掲示板に,より制限的な新しいエントリーフォームを貼り付けた。選手たちは署名を求められていなかったが,それは前兆としてそこに留まっていた。そして脅迫として。 *61

パーマーはPGAに対し,もし自身の計画が否決されれば「統一PGAの可能性はすべて終焉を迎えることになる」と警告していたが,PGAは9月13日にまさにそれを実行し,IGSAの提案を受け入れたと発表した。 *62

選手たちは即座にそれを拒否した。「私たちは団結を維持するためにできる限りのことをしてきた」と,ニクラウスは語った。これにディキンソンは次のように付け加えた:「我々は我々のことをやる。来年のスケジュールを調整中だ」。「深く失望した」と,パーマーはAPGについて述べた。そして,PGAにとって状況はさらに悪化した。退任するIGSA会長のアンガス・メアーズは,自分の団体が今後どうするかとの質問に対し,「私たちは踊り子たちと協力することに決めた」と語った。 *63

7. フォールアウト|The Fallout

エルビンは負けた。「私たちはPGAサーキットのすべての所有者の管財人として,法的手続きを含むあらゆる適切な手段で権利を守ることを誓います」と,彼は述べた。翌日の9月24日,デラウェア州連邦地方裁判所は,APGに対して一時的接近禁止命令を出した。しかし,裁判官はスポンサーが意図を明らかにするのを止めることができず,9月26日,シーパインズは1969年にAPGイベントを主催すると発表し,5つのトーナメントからなるグループのディレクターは,彼らもAPGに切り替えると述べた。 *64

10月2日,PGAはサム・スニードからの書簡を発表し,その中で彼は非公認トーナメントには出場しないと誓った。「この年齢でこれまでよりも多くの賞金を獲得できたという事実は,現在運営されているPGAツアーが生計を立てるのにかなり良い方法であることを示しているようだ」と,56歳のスニードは書いた。その年彼は,賞金43,000ドルを獲得していた。「このカントリーボーイにとって,ゴルフはとても良いものだった」。その後数週間にのあいだに,ウォルター・ヘイゲンとボビー・ジョーンズもPGA側につくことになる。 *65

裁判官がスニードの俗っぽい証言を見たとしても,感心しなかっただろう。24時間以内に彼は接近禁止命令の一部を取り消し,10月14日に残りの部分も取り消した。 *66

月が経ち,APGに切り替わるトーナメントが増えるにつれ,旧勢力はプレッシャーを感じはじめた。スポンサーは新たな契約に足を踏み入れていた。アーリッジとABCは提携から手を引くと脅していた。デイトンは 1969年の PGA Championship の開催地となる予定だったが,その二大スポンサーは,PGAが有力選手を保証できない場合は撤退すると騒いでいた。 *67

彼らはPGAのメンバーであり,PGA Championship もメジャーでありつづけたため,選手たちはデイトンに参加することを誓約し,それがPGAを助け,影響力を与えた。PGAはすぐに,PGAイベントと同じ週に開催されたAPGイベントに出場したメンバーを,会員規約に違反するとして訴訟すると発表した。APGは屈することなく,20のトーナメントの契約を結んでいると発表し,さらに13のスポンサー候補と交渉中であると発表した。 *68

この作戦は,敵対的にもかかわらず,両者には協力的な取り決めを好む理由があることを示唆していた。そして交渉が再開された。 11月中旬のPGA年次総会でのスピーチで,エルビンはある種の譲歩を示した。「我々はコントロールを共有することを望んでいる」と,彼は言った。「しかし,選手たちは今のところ支配的なコントロールを主張している」。 *69

これが,この問題に関する彼の最後の公のコメントとなった。彼はPGA会長としての任期の終わりを迎えていた。後任にはレオ・フレイザーが就任した。 *70

8. 再生|The Rebirth

偶然か否か,エルビンがいなくなると対話のペースが上がった。12月,ゲイツはスコッツデールで開催されたPGA初のクラブプロ全国選手権大会に姿を現し,そこで執行委員会が会合していた。最初のAPGツアーの開始まで,残り1か月。 *71

ゲイツ氏は15項目の計画を提示した。PGAは12の修正案を提出した。月曜日の午後に始まり火曜日の朝まで続いた15時間の会議で,詳細のほとんどが詰められ,12月12日,ついに終戦が宣言された。 *72

PGAは独立したトーナメントプレーヤー部門を設立し,プレーヤー4人,PGA幹部3人,コンサルティングビジネスマン3人からなる10人のメンバーからなるトーナメント政策委員会によって運営される独立法人を設立することになる。コミッショナーはツアーを運営し,理事会にのみレポートする。すべてのAPG契約とそのトーナメントスケジュールはPGAに移管され,係争中の訴訟はすべて却下されることになる。 *73

USGAの尊敬されるエグゼクティブディレクターであるジョー・デイがコミッショナーとして採用され,波乱を静め,選手たち,そして試合の社会的地位を回復することに貢献した。1974年,デイの後任にはディーン・ビーマンが就任し,その後 PGA of America との関係を断ち切り,運営名をPGAツアーに変更した。 *74

その後の数年間で,ビーマンは、放映権について交渉を行ない,非営利の地位を確保し,ツアーをNBAやNFLと同じくらい認識できるロゴを持つブランドに変えるなど,現代のツアーを生み出す変化を起こしました。しかし,単なる魅力とお金だけではなく,その数十年間で安定性と深みがもたらされ,より多くのイベント,育成ツアー,選手年金プランが提供された。1968 年に PGA of America を見つめた先駆者にとって,後者の点はより大きな成果だ。タイガー・ウッズが1億1100万ドルの賞金を稼いだことを,彼らは喜ぶだろう。ブライアン・ゲイやボブ・エステスのような普通の選手が2000万ドル以上を獲得したことに,彼らは興奮するだろう。 *75

「これまでのツアーで起こったことの中で最高の出来事だった」と,ゴールビーは言う。「これまでの成功と賞金の額を見てみると,その大部分はこれらの日々から持たされたと分かるだろう」。 *76

*1:“That verbal attack recently un-leashed on me by Leo Fraser, the secretary of the Professional Golfers Association, was, on the whole, inaccurate. Fraser did spell my name correctly—Jack Nicklaus. He even had my age right—28. And he signed his own name properly—Leo Fraser. The rest of his cutting statement, though, was a personal assault.”

*2:Thus began an essay in the September 16, 1968, issue of Sports Illustrated in which perhaps the game’s greatest player took on one of the PGA’s highest-ranking officials. It was one of many salvos fired during a player rebellion against the organizing body that lasted almost two years, wiped out the 1968 player of the year award, generated multiple legal actions and divided the PGA forever.

*3:What caused the trouble? What else? Opportunity, money, power—control. What would result from the epic and bitter showdown? The pro game we know today, with its tournaments named for corporations, charity partners, hospitality pavilions, luxe courtesy cars and purses so fat that in 2017 the 102nd finisher on the money list (Steve Stricker) earned more than a million bucks ($1,002,036) in 13 starts.

*4:“A lot of the players were originally against taking on the PGA,” says Bob Goalby, 89, who as a member of the Tournament Committee was one of the movement’s ringleaders. “The players who didn’t serve on the leadership committees didn’t see what was going on, but once they saw and heard the truth, they were onboard.”

*5:As the battle lines hardened, Nicklaus emerged as a leader among the more than 200 players threatening to take their balatas and bail if they didn’t get a better deal from an organization built by and run for club pros. PGA president Max Elbin led the old guard, supported by the non-touring members of the PGA and stalwarts such as Walter Hagen, Sam Snead and Nicklaus’s boyhood idol, Bobby Jones. The most powerful player in the game at the time, Arnold Palmer, was caught in the middle.

*6:“What drove the original rift?” asks Deane Beman, 80, who played the tour from 1967 to ’73. “There were 200 players playing for their life, intertwined with 6,000 club pros with steady jobs, and the needs of those two groups no longer aligned.” The question that would decide the struggle was a simple one: Which group needed the other more?

*7:At the height of the hostilities, Elbin, the head pro at Burning Tree in Bethesda, Md., showed no sign of giving in. “Some of those who have precipitated the difficulties may be surprised to find out how little time will be required to develop a new crop of capable players.”

*8:Not to be outdone, Sam Gates, a New York lawyer retained by the players, was more succinct if not entirely respectful when asked who had the upper hand. “This,” he said of the breakaway group, “is where the dancing girls are, isn’t it?”

*9:The Professional Golfers’ Association of America formed in 1916 as an organization of golf pros—people who ran pro shops and gave lessons. Many clubs in the northern states closed for the winter, so the pros who toiled there would head south to pick up extra work and compete in tournaments. The PGA began to organize the events, and by the 1930s a winter tour had become somewhat stable, with a number of annual dates and a steady stream of players.

*10:Still, the small purses, usually put up by chambers of commerce or resorts looking to stoke tourism, were not enough for anyone to live on, and when the weather turned, players went home to their “real” jobs. That remained true until the 1950s, when the schedule of events had expanded and the purses had grown large enough that some players decided to go out on tour full time. Suddenly, the PGA was comprised of two groups: golf pros and pro golfers.

*11:Through the ’60s, the gulf between those two factions grew wider, aided by demographic shifts and the convergence of two transformative forces: the swashbuckling Palmer and TV. In 1958, the total prize money available on tour sat at $1 million; by ’68 it had hit $5.6 million. Competition for that cash was Darwinian. Each year, tournament winners and the top-60 money earners from the previous season were granted exempt status, but otherwise fields were filled by one-round, top-scorers-get-in Monday qualifiers.

*12:Those qualifiers were open to both tour regulars and to any local PGA member who wanted to take a week off from the pro shop and try to win a trophy. By 1964 there were so many players on the tour and so many local pros vying to get in fields—and so much complaining from tour regulars—that the PGA created a qualifying tournament (later called Q School) through which players could earn a tour card. Cardholders did not join the ranks of the exempt, but they could enter Monday qualifiers for $100 while non-cardholders now had to pay $200. In addition, the number of slots available to non-cardholders was capped.

*13:Most fields topped out at 144 or 156 players, which meant that after exempt players were accounted for, as many as 150 guys were battling for 50 to 75 spots each week. For the touring pros the stakes were high. Whether they qualified or not, they had to throw down for the entry fee, food, travel, lodging and a caddie.

*14:Players coveted any opportunity to earn a check, so they were excited when, in 1966, Frank Sinatra offered to sponsor a new $200,000 tournament in Palm Springs. What was then known as the PGA’s Tournament Bureau was run by the Tournament Committee, made up of four players and three PGA executives—Elbin, Fraser and treasurer Warren Orlick. In a 4-3 vote, the committee decided to add the Sinatra event to the schedule.

*15:Elbin was against the Ol’ Blue Eyes plan because the event would take place within a few weeks of the already existing Bob Hope Desert Classic, also in Palm Springs, and Hope himself had called to say he didn’t think both events could survive. Decisions of the Tournament Committee were subject to the vote of the full, 17-member PGA Executive Committee, comprised of 16 officials and one player. Instead of waiting for that group’s next gathering, Elbin called for the four Executive Committee members on hand—the three officers and the player rep—to vote representing the full committee in absentia. By a count of 3-1, the ad hoc Executive Committee overruled the Tournament Committee.

*16:The players protested. “We run all the risks,” one tour competitor told SI at the time, “so why should we have a bunch of armchair club pros telling us we can’t play a $200,000 golf tournament?”

*17:The touring pros also took issue with a new $250,000 tournament in Westchester, N.Y., that PGA executives had negotiated in secret and from which $50,000 of the purse was supposed to go into a general pension fund for all PGA members. The plan was scrapped, but the damage was done.

*18:To the PGA, the Sinatra event represented just cause for using its veto power for the first time its 52-year history.

*19:To the players, it was an act of war.

*20:Discord broiled through the end of 1966 and into early 1967. Touring pros chafed at the binds imposed by the “sweater folders,” while club pros grew weary of the “prima donnas” who teed it up on TV. “As a member of the tour, I didn’t feel very comfortable for a while going into some pro shops at golf clubs,” says Kermit Zarley, 76, who joined the tour in 1964.

*21:“The problem was that the whole operation was being run part-time by three club pros,” says Goalby. “They didn’t have the time to handle everything we needed—from pensions to course setup—and when they did, they approached it as a club pro would.” Even more than Elbin, Orlick and Fraser, tour members took issue with Robert Creasey, a former assistant secretary of labor in the Truman administration who, against the players’ wishes, was appointed tournament manager and executive director by the PGA.

*22:Creasey had a key role in negotiating the disputed Westchester event, and the players felt he was symbolic of the high-handed approach PGA officials took toward the tour. They complained that he tried to make himself the “czar of golf,” getting his fingers in everything from TV deals to scheduling. Goalby remembers one meeting particularly well: “We were talking about the expenses charged to the Tournament Bureau, and Creasey says, ‘When Bob Creasey travels, he goes double first class.’ That didn’t sit too well with a lot of the guys.”

*23:The bad feelings came to a head in Memphis on June 1. The players produced a seven-point manifesto demanding control over scheduling, finances and the hiring of tour-related personnel. Most of all, they insisted on taking away the PGA’s veto power. In all, 135 players signed it, and added an ultimatum: If the PGA didn’t agree to all their points by June 15, the players would boycott the 1967 PGA Championship, scheduled for July 20 at Columbine Country Club, near Denver.

*24:The next day Elbin told the press that the PGA would consider the document. Since June 15 was the first day of the U.S. Open, he arranged to meet with the players on June 20 in Cleveland, but not before amping up the rhetoric by calling the tour leaders “agitators” and noting “many of the players are following blindly a trail baited with half-truths, insinuations and outright lies.”

*25:The sides traded jabs for the next two weeks. Elbin sent a letter to players suggesting they could be suspended if they boycotted, which Doug Ford, the 1957 Masters winner and the players’ unofficial “grievance chairman,” said the players “laughed at,” since by rule the harshest punishment one could receive for skipping an event he’d committed to was a $100 fine.

*26:The build-up led to an unusually tense Open week at Baltusrol, in Springfield, N.J. “Palmer, defending champion Bill Casper, and other stars of the game rushed in and out of a closed-door meeting with PGA brass between practice rounds,” reported the Spartanburg Herald on June 14. Casper hadn’t signed the petition, but only because he wasn’t in Memphis at the time. “I’m with the players,” he told reporters. “They’ve got my vote.”

*27:Such solidarity proved essential in Cleveland. In meetings that stretched nine hours and included bitter words and several stalemates, one final session led to a compromise: The seven-man Tournament Committee would become an eight-man group, with four players and four PGA executives. Voting ties and disputes would be settled by a new three-person advisory board whose members would be nominated by players and approved by the PGA. The players got six of the seven demands in their manifesto, including Creasey’s dismissal as executive director, but the PGA’s veto power remained intact.

*28:“It’s a good settlement,” Ford said afterwards. “We are happy with it.”

*29:The joy wouldn’t last.

*30:Players continued to grumble about the surviving veto power. On July 1, Ford announced that tour members had taken another vote and elected to disavow the Cleveland solution. They played in the PGA Championship but never appointed an advisory board, and they still wanted the Executive Committee stripped of its control. The accord both sides thought they had reached in Cleveland lasted all of 14 days.

*31:At a subsequent player meeting, Al Geiberger announced that he had a friend named Philip Freeman who worked as a management consultant, and that Freeman had volunteered to spend three weeks analyzing the situation and identifying the sticking points by interviewing players, sponsors, tournament officials and PGA members. He would then produce a proposal to solve the problems.

*32:On August 8, 1967, Freeman filed a 23-page report that recommended that the PGA and the Tournament Division become two separate entities housed under one roof. The PGA would continue to operate with its current structure and the tour would be overseen by a board of players and outside experts who’d hire a commissioner to run its day-to-day operations and long-term business. He suggested that the players hire a lawyer to represent them in negotiations.

*33:The players read the report but took no action, at least not until the PGA’s annual meeting in Palm Beach, Fla., in November, where Elbin gave a speech that included a warning: Follow the rules or “get out.”

*34:His stance, he explained, came in part because he was “tired of being harassed.” If it wasn’t clear that he was referring to the tour players, he proceeded to introduce a new tournament entry form that limited players’ rights and required anyone who qualified for the PGA Championship to play in it. “Entrants in our regular tour events will be considered to have an obligation to compete in our championship,” he said. Call it the anti-boycott clause.

*35:The plan for an expanded eight-person Tournament Committee agreed to in Cleveland survived, and during the annual meeting, the players filled out their half with Gardner Dickinson, as chairman, Doug Beard, Ford and Nicklaus; the executive half consisted of Elbin, Orlick, Fraser and vice-president Noble Chalfant. The group spent the winter sparring over the USGA’s new putting rules—the executive committee gave its initial approval but the players were vehemently opposed—and the new tournament entry form.

*36:When the Crosby Clambake kicked off the 1968 season in January, neither issue had been resolved. The players hired Gates, who advised them not to accept the new form. Faced with a mass revolt backed by legal muscle, the PGA sided with the players on the putting rules and reverted to the old entry form. It also hired its own representation: a Washington lawyer named William Rogers.

*37:For the next few months, Gates and Rogers carried on the conversation while assuring all parties they’d be able to negotiate an amicable settlement. “We phoned and met a great number of times,” Gates said. “There was never any acrimony between us.”

*38:The peace was not contagious. Rumors circulated that the players were considering the nuclear option: dumping the PGA entirely and starting their own tour. As if it was daring the players to go, the PGA rehired Bob Creasey as executive director in late July. Word spread that he had negotiated a $100,000 TV deal for the World Series of Golf and Shell’s Wonderful World of Golf without consulting the players, and that the money would go not to the Tournament Bureau but into a general PGA fund. Players argued among themselves. “Some of those meetings got emotional,” recalls Zarley.

*39:After he missed the cut in the PGA Championship at Pecan Valley in San Antonio, Jack Nicklaus was asked what he thought of the field, which included 112 club pros and only 56 touring pros. “It’s absurd and unfortunate,” the Golden Bear growled, which rankled the PGA.

*40:In early August, the situation grew even worse.

*41:Rogers and Gates had sketched the framework of a self-governing tournament division operating under the roof of the PGA. Sorting out the details of exactly how autonomous the division would be was the hard part. Since any amendments to the PGA constitution had to be filed 100 days before November’s annual meeting, Gates offered a placeholder resolution on August 6, 1968, to ensure that the issue would be on the docket. In part, the document called for a Tournament Players Section of the PGA, “which shall have full and complete authority over the conduct and management of the PGA Tournament Programs.”

*42:Elbin and his colleagues voted it down.

*43:Gates was incensed. “It was a simple item on the agenda, which should not have taken two minutes,” said Gates at the time. “The action was designed only to keep the door open for further negotiations. But the PGA officers slammed it shut in our faces.” He continued, “In so doing the officers completely undermined all the months of patient work between Rogers and myself and all the progress we had made toward a fair settlement of our differences. In a display of bad faith, they kicked over the traces.”

*44:“The players now wanted to be completely autonomous from the rest of the PGA,” Elbin responded. “This was completely unacceptable.” The following week Gates went to Washington D.C. to meet with PGA executives, who offered an eight-point plan that seemed to be an attempt to revive the Cleveland agreement. In it, they proposed creating an advisory board that would arbitrate disputes. But the plan gave the PGA a controlling majority on the board, in effect maintaining its veto power.

*45:This time Gates rejected the deal. Further negotiations fell apart, and later that day more than 100 players, gathered for the Westchester Classic, held a vote. The question at hand was the future of professional golf in the United States. By a unanimous count the tour pros went nuclear.

*46:“I have 205 clients—I have counted them. We are negotiating for tournaments and television contracts now. We will have announcements when they are completed.” It was August 19, six days after the players had voted to break away, and Gates was holding a press conference to introduce APG—American Professional Golfers, Inc. A 13-member APG advisory committee—comprised of Dickinson, Nicklaus, Beard, Ford, Casper, Goalby, Zarley, Jerry Barber, Lionel Herbert, Dave Eichelberger, Dave Marr, Bob Rosburg and Dan Sikes—had been created.

*47:Gates announced that the players would play out the remainder of the season, plus the two tournaments already under contract for 1969. “Our boys have no intention of resigning from the PGA,” he said. “The players will not boycott any tournament, because that would not be in the best interests of the game and of the public.”

*48:“We don’t want to strip the PGA of its representation,” was how Dickinson put it. “What we want is to have the right to cast the deciding vote over such matters as where, how and under what conditions we play. It seems like a reasonable request to me.”

*49:Elbin didn’t think so. Two days earlier, the PGA had disbanded the Tournament Committee and seized control of the tour, and it scheduled its own press summit for the same day as the APG’s. “I can’t see their desire to escape the PGA,” Elbin said. “I don’t understand it. The PGA has made millionaires out of some of these men.”

*50:Elbin left no room for straddling the line. “If a player decides to go with the other group, his PGA card will be lifted immediately.” As for what would become of the PGA events, he said, “We will continue to play tournament golf. It will be tough at first, but we will endure.”

*51:Along those lines, Fraser noted that the PGA still controlled the club pros and therefore the clubs. “We’ve got 6,000 little factories turning out potential stars,” he said.

*52:The next day Elbin proposed a new tournament entry form that would force players to commit to the PGA. A resigned Dickinson admitted, “there is no chance as of now of a reconciliation.”

*53:No one seemed more conflicted by the split than Arnold Palmer. He’d publicly supported the players but maintained a dialogue with both sides. “He was selling clubs, so it was hard for him to alienate the club pros,” says Goalby. “He had to worry if they were going to stop carrying his stuff.”

*54:Besides selling clubs, Palmer had lucrative endorsement deals and widespread notoriety beyond golf, and he and his agent, Mark McCormick, were leery of being seen in a negative light by the public. Most of all, Palmer’s father, Deacon, was the head pro at Latrobe Country Club and a long-time PGA member. The organization meant a lot to Palmer personally, and he felt compelled to make peace. “I think that the pros and the PGA need each other, and there should be further negotiations,” he said after the formation of the APG.

*55:Palmer began working the phones, and on Friday, August 23, Elbin flew to Latrobe to meet with him. Six days later, Palmer returned the favor, jetting to D.C. to make a presentation to the PGA Executive Committee. Palmer wasn’t representing the APG, but Gates signed off on the trip. “My purpose as an individual is to try to find a solution,” Palmer said.

*56:In a closed-door session that lasted four and a half hours, Palmer made the case that the two groups should merge for a one-year trial, during which the tour would be run by a 14-person board consisting of the APG’s newly elected seven player/directors—including Dickinson as president and Nicklaus as vice president—four unaffiliated businessmen, and three PGA officers. Elbin promised that the full PGA Advisory Board would discuss the proposal at its meeting in Houston on September 6. “Any time you talk to Arnold Palmer,” he said, “it’s a step in the right direction.”

*57:“Arnold controlled a lot about golf in those days,” Goalby agrees. “Other players respected his opinions.” If Arnie had said he was sticking with the PGA, many would have followed suit.

*58:But golf’s other big star had already moved on. While Palmer was negotiating, Nicklaus insisted that the APG would move forward with its plans. That caused Fraser to accuse Jack of trying to undermine Arnold’s efforts. Fraser’s claim that Nicklaus had disseminated “false information designed to mislead the public,” among other things, led to the Golden Bear’s scathing, 1,500-word rebuttal in Sports Illustrated.

*59:Outside the big two, other powerful forces were stirring. The International Golf Sponsors Association (IGSA), which represented the money behind 34 of the PGA’s 44 events, cautioned both sides not to jeopardize the rest of the 1968 season. At ABC, which had just signed a two-year deal to televise ten tour events, including the PGA Championship, Roone Arledge, then the network’s VP for sports, piped up. “I’m not sure how the present controversy will affect us,” he said, “but we won’t televise a tournament with nobodies in it.”

*60:Houston turned into a problem. The IGSA was holding its annual meeting in the city in conjunction with the PGA Advisory Board meeting. So as the debate on Palmer’s proposal commenced, the sponsors offered up a solution of their own. It was a variation on the theme: A separate tour division, in this case governed by a 12-member board made up of three current players, three retired players, three PGA executives and three officers of the IGSA.

*61:Faced with a new option, the PGA delayed its decision. Meanwhile, at the Greater Hartford Open, in Connecticut, officials tacked a new, more restrictive entry form to the bulletin board. Players hadn’t been asked to sign it, but it hung there as a harbinger—and a threat.

*62:Although Palmer had warned the PGA that if it voted down his plan, it will have “written a finish to any possibility of a united PGA,” the PGA did just that on September 13, announcing that they had accepted the IGSA proposal.

*63:The players quickly rejected it. “We have gone as far as we can go to try to keep together,” Nicklaus said. To which Dickinson added: “We’re going ahead with our business. We are in the process of making a schedule for next year.” A “deeply disappointed” Palmer sided with the APG. And it grew worse for the PGA. When asked what his organization would do, Angus Mairs, the outgoing president of the IGSA, said: “We have decided to go with the dancing girls.”

*64:Elbin lost it. “As trustees for all the owners of the PGA circuit, we pledge ourselves to defend our rights by all proper means, including legal procedures,” he said. The next day, September 24, the United States District Court in Delaware issued a temporary restraining order on the APG. The judge, however, could not stop the sponsors from making their intentions clear, and on September 26, Sea Pines announced that it would host an APG event in 1969, and the director of a group of five tournaments said that they, too, would flip to the APG.

*65:On October 2, the PGA released a letter from Sam Snead in which he vowed not to play in non-sanctioned tournaments. “The fact that I have been able to win more money at my age than ever before would seem to indicate the PGA tour is a pretty good way to make a living as it is being run right now,” wrote Snead, who, at 56, had won $43,000 in prize money that year. “Golf has been pretty good to this old country boy.” Over the coming weeks, Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones would also side with the PGA.

*66:If the judge saw Snead’s folksy testimony, he wasn’t impressed. Within 24 hours he’d rescinded part of the restraining order, and on October 14 he did away with the rest.

*67:As the month progressed and more tournaments flipped to the APG, the old guard started to feel the pressure. Sponsors were dragging their feet on new contracts. Arledge and ABC were threatening to pull out of their deal. Dayton was set to host the 1969 PGA Championship, and its two biggest sponsors were making noise about backing out if the PGA could not guarantee the marquee players.

*68:Since they remained PGA members, and the PGA Championship remained a major, the players pledged to show up in Dayton, which helped the PGA—and gave it leverage. It soon announced it would sue any member that played in an APG event that took place the same week as a PGA event, since that would be a violation of membership rules. Unbowed, the APG announced it had contracts for 20 tournaments, and was negotiating with another 13 potential sponsors.

*69:The maneuvering suggested that, despite the contretemps, the two sides had reasons to prefer a cooperative arrangement. And negotiations resumed. In his speech at the PGA’s annual meeting, in mid-November, Elbin showed some give. “We’re willing to share control,” he said, “but the players so far insist on dominant control.”

*70:It was his last public comment on the matter; he’d reached the end of his term as PGA president. He was replaced by Leo Fraser.

*71:Coincidental or not, with Elbin gone the pace of chatter picked up. In December, Gates turned up at the PGA’s first club-pro national championship in Scottsdale, where the Executive Committee was meeting. A month remained before the start of the inaugural APG tour.

*72:Gates presented a 15-point plan. The PGA came back with 12 amendments. During a 15-hour meeting that started on a Monday afternoon and went into Tuesday morning, they hammered out most of the details, and on Dec. 12 an end to the war was finally declared.

*73:The PGA would form a separate Tournament Players Division, a freestanding corporation run by a 10-member tournament policy board of four players, three PGA executives and three consulting businessmen. A commissioner would run the tour and answer only to the board. All the APG contracts, and their tournament schedule, would be transferred to the PGA, and all pending litigation would be dismissed.

*74:Joe Dey, the respected executive director of the USGA, was hired as commissioner, and he helped calm the waters and restore the players’—and the game’s—public standing. In 1974, Dey was succeeded by Deane Beman, who would go on to sever all ties to the PGA of America and change the operation’s name to the PGA Tour.

*75:In the years that followed, Beman initiated the changes that have created the modern Tour, negotiating better TV deals, securing nonprofit status and turning the Tour into a brand, with a logo as recognizable as that of the NBA or NFL. But more than just glamour and money, the intervening decades have brought stability and depth, with more events, a developmental tour and a player pension plan. To the pioneers who stared down the PGA of America in 1968 these latter points are the greater achievement. Those guys would be happy that Tiger Woods has earned $111 million in purses; they’d be thrilled that rank-and-file players such as Brian Gay and Bob Estes have taken home more than $20 million.

*76:“It was the best thing that ever happened to the Tour,” say Goalby. “When you look at how successful it has been, and all the money these guys play for now, so much of it came from those days.”